Difference between revisions of "Many Mansions"

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

[[File:Vaticana, Vat. lat. 3868 (2r).jpg|300px|thumb|left|ortrait of Terence around 823.]] | [[File:Vaticana, Vat. lat. 3868 (2r).jpg|300px|thumb|left|ortrait of Terence around 823.]] | ||

| − | Before around 1200, performances took place mainly within churches, generally as part of the church services. Performances took | + | Before around 1200, performances took place mainly within churches, generally as part of the church services. Performances took place in two main areas: small scenic structures called mansions, each indicating a location, and the ''platea'', a general acting area adjacent to the mansion. Various places within the church were used for the mansions, so the choir loft would be used for heaven, and the alter could represent the tomb of Christ. Effects, including lighting and flying, could be spectacular (A.02). |

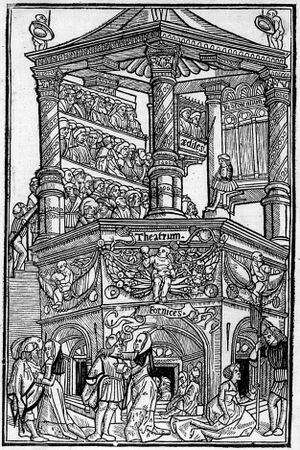

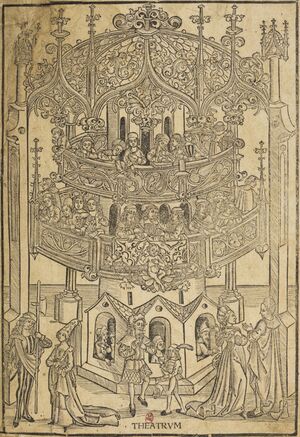

[[File:IO2 F.02 02.jpg|300px|thumb|left|Illustration of the Theater for the Comedies of Terence in the edition of Jean Trechsel of 1493. National Library of France]] | [[File:IO2 F.02 02.jpg|300px|thumb|left|Illustration of the Theater for the Comedies of Terence in the edition of Jean Trechsel of 1493. National Library of France]] | ||

Revision as of 15:07, 11 February 2023

The simultaneous and the Terence stage

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, multiple locations were denoted by ‘mansions’ on stage. The simultaneous stage and the Terence stage were superficially similar, but represent different ideas of performance space.

The simultaneous stage was a stage form of the religious plays of the late Middle Ages and remained the predominant stage form outdoors or indoors such as in the church until the Renaissance. On the simultaneous stage, all the settings were next to each other, often simultaneously.

Before around 1200, performances took place mainly within churches, generally as part of the church services. Performances took place in two main areas: small scenic structures called mansions, each indicating a location, and the platea, a general acting area adjacent to the mansion. Various places within the church were used for the mansions, so the choir loft would be used for heaven, and the alter could represent the tomb of Christ. Effects, including lighting and flying, could be spectacular (A.02).

Later, performances began to take place outdoors, with the same concept of multiple simultaneous stages – the mansions and the platea – either set up as fixed scaffolds, or on mobile wagons (E.02). The audience would gather around each stage as the story unfolded, and in the case of moving stages (known as the wagon stage, or the pageant stage), the scene would be played multiple times as the wagon moved through the town. The locations represented would be determined by the story to be enacted, but it was common for heaven and hell to be included, with hell on the left, heaven on the right, and the earthly realm in the centre. The use of the space had a significance that is unfamiliar to a 21st century audience; the medieval simultaneous stage, like simultaneous representations in the visual arts of the time, expressed a pre-modern understanding of space and time. Simultaneous actions are not parallel because they take place at the same time, but because they have a comparable significance.

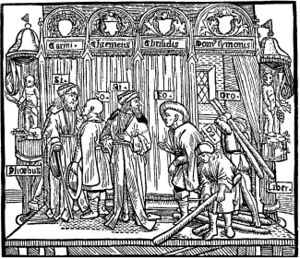

Superficially similar, the Terence stage also divided the scenic space into multiple mansions. The Terence stage is the name given to settings of the plays of Roman dramatist Publius Terentius Aphro, known as Terence, when they were revived in the Renaissance period. Because of its similarity to bathing cabins, the Terence stage is therefore also called the bathing cell stage. As in the theatre of Greek and Roman antiquity, it was intended to show the unity of the place of action, not several settings like the medieval simultaneous stage, though it also had many mansions. The Terence stage took up the stage structure of classical antiquity, which was considered idealised, following the example of the comedy poet Terence. For this purpose, it consisted of a flat podium, on the back wall of which house facades were indicated, whose construction of columns with curtains hung between them symbolised the entrances to the houses; these curtains were partly provided with inscriptions and could also reveal a view of a second scene inside the house behind them.

Publius Terentius Aphro was an author of comedies during the Roman Republic, first performed between 170 and 160 B.C. During his lifetime he wrote only six plays, all of which have survived. The genre that Terence wrote was the so-called palliate fabule, the palliata comedy, a genre inspired by Greek comedy, but with typically Roman elements: customs, costumes, laws, buildings, historical allusions, and the names of the gods.

Some of Terence’s publications in Italy and France were illustrated. The first printed edition of Terence’s comedies dates from 1470 in Strasbourg. The engravings that accompanied the editions of Terence’s dramatic works represented how the people of the Renaissance imagined ancient theatre. In the Trechsel edition of 1493 appears the idea of the theatre as a centralised building representing the symbol of moral construction. In the lower part of the engraving, vice is represented compared to virtue, reached through a staircase that leads to the theatre itself. Above, the audience and the stage are shown – the proscenium is labelled, and the mansions with their doorways and curtains are depicted.

The underlying concepts and world-view are different, but in the simultaneous stage and the Terence stage, scenic space is organised and codified in a way that would have been highly meaningful to the audience.