Difference between revisions of "In the Limelight"

(Created page with "''The industrial age brought two lighting innovations: gas light, which made the brightness more controllable; and the lime and arc lights, that could create a high intensity...") |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 15:08, 15 February 2023

The industrial age brought two lighting innovations: gas light, which made the brightness more controllable; and the lime and arc lights, that could create a high intensity ‘point source’, making it possible to focus the light into a beam.

For centuries, lighting was made only by flame based sources, mainly candles or organic oil lamps, with a limited intensity that was hardly controllable. The light sources were evenly spread over the stage area, organised in floor lights, wing lights and some chandeliers. Top light was impossible because the sources could not burn upside down. Control was only possible by covering the lights or turning them away from the stage. The light could not be focused and directed as a beam. By the end of the 19th century, all that had changed.

The first use of gas light (Q256) in a theatre is contested, but was around 1816-17. The first gas lighting burners were rather rudimentary, producing a large round (‘rats tail’) or flat (‘bat wing’, ‘fish tail’) open flame that generated a lot of risks for the actors as well as the building. The accident in Philadelphia’s Continental Theater in 1861 (Q315) where the ballerinas caught fire is just one example of many. The later adaptation of the Argand burner (Q30615) for gaslight provided a glass chimney, ensuring a better combustion and producing more light with less danger. The burners were connected to the gas system with iron pipes for fixed positions or flexible leather tubes for movable equipment.

An advantage of gas lighting is that the flame can burn upside down. For the first time, border lights, lighting the stage from the top, could be used. Together with wing lights, footlights, and ‘all sorts of special form and size to suit particular pieces of built scenery’, they formed the basis of the lighting plot. In the auditorium, the main chandelier was replaced by a ‘sun burner’ and the lights on the sides with smaller burners. These could also be controlled along with the stage lighting, which made it possible for the first time to darken the auditorium.

Control was done with a simple gas table, a set of valves with a master valve. By controlling the amount of gas, the intensity could be adjusted. A valve would control one, two or three rows of burners. Later, small pipes were added to ensure a pilot flame would stay lit if the burners were extinguished, so allowing complete blackouts during the performance. Bram Stoker (Q258) states in his essay on Irving and lighting (Q259) that darkness was ‘found to be, when under control, as important a factor in effects as light’. Changeover could, from this moment on, be done in darkness, without closing the curtain. The stagehands were therefore given ‘dark clothes and silent shoes’.

The arrival of lime light (Q176) in the 1830s changed the way lighting was used on stage. For the first time, a high power point source was available, so it was possible to make full use of optical systems, focus the light in a specific direction, put an actor ‘in the spotlight’ or reveal the dimensionality of an object. Shadows became sharp, defined and visible, and the full range of colours became readily discernible. Effects such as Pepper’s Ghost (B.05, Q305) could be achieved. Projections on stage became powerful enough to be combined with stage lighting.

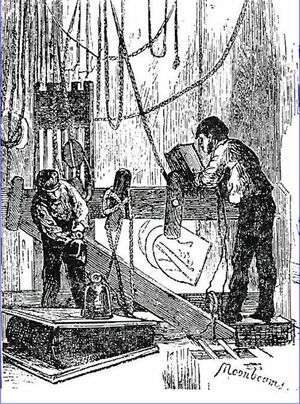

The luminous source of a lime light is a block of lime heated at a point by an oxygen-hydrogen burner, creating an intense white light. This point source can be placed in the focal point of a concave mirror to create a powerful beam (open lime), or the light can be concentrated and directed using a lens. In both cases a beam is created that can’t be created with flame based light sources. The lime light needed the constant attention of an operator to control the gas pressure and the burner, and turn the lime block, so the lime light was used more like a modern-day follow spot than like a spotlight. Lime lights were expensive to run, and could only be placed where a human operator could reach them, so the general lighting of the stage continued to be gas light, with limes for effects.

The carbon arc lamp (Q232) was the first electric light used on stage, creating an intense blue-white light from the discharge between two carbon rods fed from a DC power supply. As the use of electricity for other applications grew, and electricity supplies became more readily available, carbon arc lamps replaced lime lights as a focused source of light from the 1880s, with all the same benefits as limes.

The 19th century brought great change to stage lighting, with the move to gas for general lighting and the introduction of lime and arc lamps for directional, focused light for the first time. The fundamentals of today’s stage lighting were in place – focused and controllable light – ready to be developed and refined with the complete electrification of lighting that followed.