Making room for infinity in the Teatro Olimpico[edit]

The Teatro Olimpico is the oldest of only three surviving Renaissance theatres. The innovative scenery was the first use of false perspective in a Renaissance theatre; to accommodate it, an extension to the rear of the theatre had to be built.

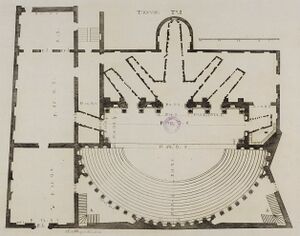

The Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza (Q650) was commissioned by the Olympic Academy and designed by Andrea Palladio (Q651). Palladio, a founder of the Academy, had already designed temporary theatre structures at various locations in the city, and drawn plans for theatres following the patterns of Roman and Greek architecture through the writings of Vitruvius (Q467). In 1579, the Academy obtained the rights to build a permanent theatre in an old fortress, the Castello del Territorio. Despite the awkward shape of the old fortress, Palladio decided to use the space to create a reconstruction of the Roman theatres that he had so closely studied, including the full Roman-style scenae frons back screen across the stage. This however was to be made from wood and stucco, imitating the Roman marble.

Construction of the Teatro Olimpico began in February 1580, but in August of the same year Palladio died, with the works well advanced. Vicenzo Scamozzi, another important architect in Vicenza, took over the project, making some additions to and changes to Palladio’s designs. For the opening performance, Oedipus Rex by Sophocles was chosen, and Scamozzi designed the scenery. Representing the play’s location in the city of Thebes, and following the precepts of Peruzzi and Serlio (Q568), Scamozzi’s innovative designs created seven streets built in exaggerated perspective, each starting from one of the five openings of the Scenae Frons, and running away from the stage. The streets were so arranged that from every seat in the auditorium, at least one street could be viewed, while the remarkable trompe-l’oeil painting gave life and dimension to the scene. Scamozzi not only designed the sets, but also put considerable effort into designing the lighting that permitted the houses of the stage scenery to be lit from within, completing the illusion that these were real streets. The lighting for Oedipus Rex is one of the first times that artificial lighting in theatre by cobbler ball lenses (Q30518) with coloured liquids is documented.

The realisation of Scamozzi’s designs faced one, rather unusual, obstacle, however. Even with the compression of the false perspective, the streets could not be fitted within the original stage space or indeed the theatre building – an extension would be required. Furthermore, the Academy did not own the land on which the scenery was to be built. This land was acquired in 1582, after Scamozzi had taken charge of the project. This made it possible to extend the building (including a special apse-shaped projection to accommodate the longest and most elaborate of the seven street views). The Academy’s petition to the city government for the additional land anticipated that if acquired, the space would be used to create perspective scenery; it explained that the extra land would be used to build a theatre ‘along the lines laid out by our colleague Palladio, who has designed it to permit perspective views.’ The land was obtained, the theatre extended, and Scamozzi’s perspective streets, disappearing apparently to infinity, were installed.

The Teatro Olimpico was little used for performances after Oedipus Rex, and has survived largely intact, together with Scamozzi’s setting – the oldest surviving stage scenery. It is still used for plays and musical performances, but audience sizes are limited to 400, for conservation reasons. Over the centuries, the Teatro Olimpico has had many admirers, lots of influence, but relatively few imitators. The first theatre to draw inspiration from the Teatro Olimpico, and the one in which its influence is the most obvious, is the Teatro all’Antica, Sabbioneta, Italy (Q653), also designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi. The English architect Inigo Jones (Q20471) visited the Teatro Olimpico shortly after its completion, and took careful notes, in which he expressed particular admiration for the perspective views.

Scenic designers must usually fit their designs into the available space of the theatre. However, there have been times when theatres have been modified to accommodate the scenography, such as knocking a hole in the back wall of the stage to give a greater throw for back projection. The Teatro Olimpico is the first and perhaps greatest example of the theatre building being fitted to the stage design.