Difference between revisions of "Architecture Codified"

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 20:35, 10 January 2023

The books of Vitruvius

In De Architectura, Vitruvius codified Roman architecture, setting out principles and practical considerations for buildings and civil engineering of all kinds, including theatres. Revived in the Renaissance, its impact can be traced to the present.

Marco Vitruvius Pollio was a Roman architect, writer, engineer and treatise writer from the 1st century BCE. He is the author of the oldest treatise on architecture that is preserved, and the only one from classical Antiquity. De Architectura (Q467) consists of ten books, probably written between the years 27 BCE and 23 BCE, and dedicated to the Emperor Augustus.

The ten books cover not only architectural design and the orders of architecture (the appropriate styles, proportions and functional requirements for various types of buildings), but also town planning, civil engineering, the qualifications required of an architect or the civil engineer, building materials, pavements, decorative plasterwork, water supplies and aqueducts. He also writes about the sciences influencing architecture – geometry, measurement, astronomy, the sundial – as well as the use and construction of machines, including Roman siege engines, water mills, drainage machines, hoisting, and pneumatics.

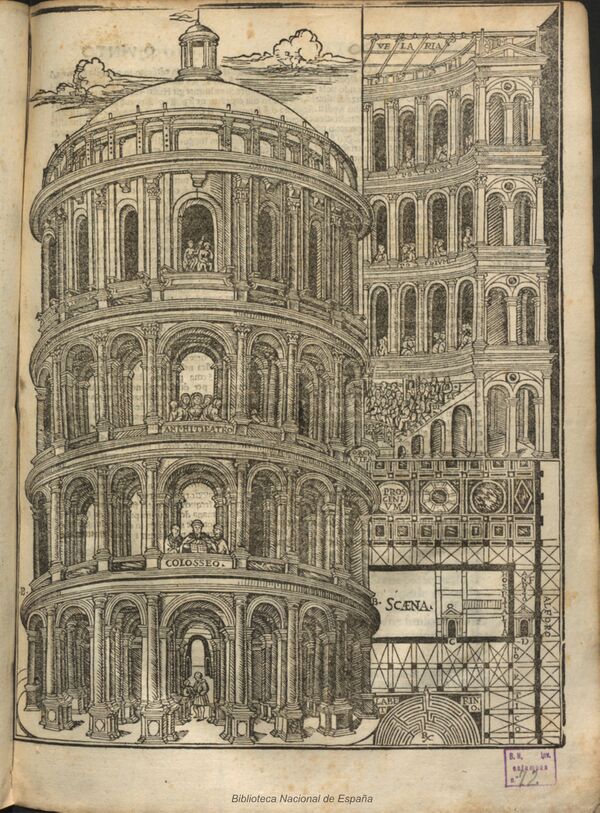

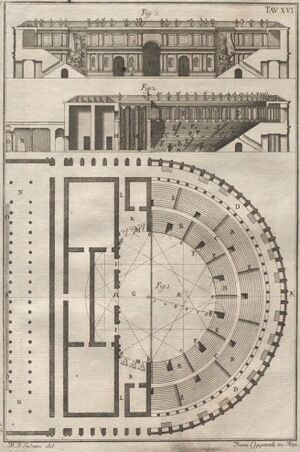

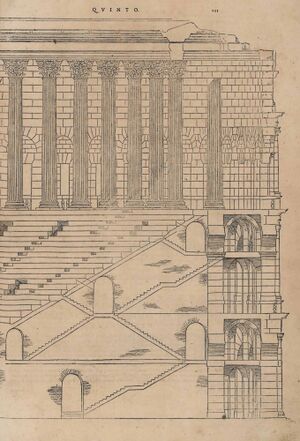

In book V, Vitruvius give a detailed account of the architecture and technical workings of Roman theatres of his time. He dedicates chapter III to the site, foundations and acoustics of the theatre, while chapters IV and V cover the theory of musical harmony, and the use of sounding vessels of the theatre as an acoustic treatment (D.01). In chapter VI, Vitruvius details the plan and proportions of the theatre, and in VII he compares the Roman theatre with earlier Greek theatres. Chapter VIII returns to the subject of acoustics, and IX describes the colonnades and walkways behind the stage.

Vitruvius asserts that the auditorium should be a semicircle (emiciclus) with rising tiers of steps that act as seats, and a colonnade surrounding the highest level. At the back of the stage is an architectural construction, with rows of columns ex domorum imitatione.

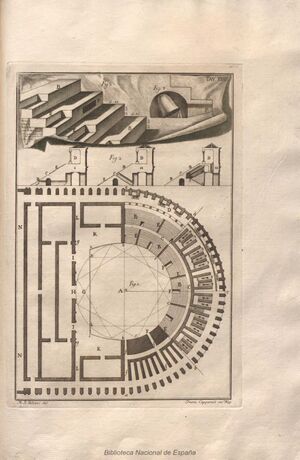

He writes about theatre acoustics and develops acoustic principles by explaining how sound waves spread out in space just as waves spread out in water. And as for the sounding vessels of the theatre he says that they have to be constructed in such a way that when they are touched they produce a sound from one to the other according to a sequence or harmonics.

Vitruvius does not give the measurements of the theatre but the proportions between the different elements that compose it, which start from a basic dimension: the diameter of the orchestra. It starts from the complete circumference of the orchestra on a flat area. The diameter of the circumference is chosen by the architect who defines the dimensions he wants for the theatre. The only fixed dimension is the height of the stage (no more than five feet) and the steps of the seats, which must be no less than 10 inches and no more than 18 inches, and their width must be between 2 and 2.5 feet.

As far as the setting is concerned, he mentions the scenae frons (Q23705) with its three doors and the three types of scene: tragic, comic, and satirical. He also describes the periaktoi (Q23827):

The scene will have this arrangement: the middle gate will be magnificently adorned as a royal palace. Right and left are those of the guests: next to these doors are the spaces for decorations. The Greeks call them periaktoi, because in them the machines are placed on versatile triangles, and each one has three different decorations, which turn, and change as appropriate, when the fable begins, or when the coming of the Gods is feigned with sudden thunder, making a different scene and ornament appear. Next to the aforementioned spaces run the angles through which the scene is given transit, one for those who come from the forum, and the other for those from other parts. (Q467, book V, chapter VII)

De Architectura was not totally forgotten during the Middle Ages, but it was rediscovered in Saint Gall by Poggio Bracciolini in 1414. As a result, Alberti, in his De re Aedificatoria (Q30509), around 1450, was able to base his treatise on the theatre on Vitruvius. De Architectura was first printed in Rome in 1486, and the first illustrated edition in Venice in 1511. In the same years as the first edition of Alberti and the first edition of Vitruvius, efforts were made to rediscover the Roman models of architecture, as well as the rebirth of the works of the Roman playwrights, especially Plautus, Terence and Seneca.

Vitruvius’s De Architectura is the oldest known systematic description of architecture and engineering, it not only gives an insight into Roman practices and technologies from the 1st century BCE, but its influence can also be traced, via the Renaissance, to modern day architecture and the design of theatres.