Difference between revisions of "G.04 How to build a Theatre"

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

[[File:Fotothek_df_tg_0006993_Mechanik_%5E_Bibliographie_%5E_Portr%C3%A4t.jpg|200px|thumbnail|left|Joseph Furttenbach]] | [[File:Fotothek_df_tg_0006993_Mechanik_%5E_Bibliographie_%5E_Portr%C3%A4t.jpg|200px|thumbnail|left|Joseph Furttenbach]] | ||

| − | Joseph Furttenbach the Elder was a German architect, mathematician, engineer and diarist. From 1607 to 1620 he stayed in Italy, where he did an apprenticeship as a merchant under the supervision of his uncles. Moreover, he studied engineering, military architecture and grew an interest in theatre and stage design while abroad as well as festivals, processions, pyro technics and dramatic performances. Back in Germany, he had a successful career as an architect, universal engineer and writer. He designed a hospital, a waterworks system, a theatre, and | + | Joseph Furttenbach the Elder was a German architect, mathematician, engineer and diarist. From 1607 to 1620 he stayed in Italy, where he did an apprenticeship as a merchant under the supervision of his uncles. Moreover, he studied engineering, military architecture and grew an interest in theatre and stage design while abroad as well as festivals, processions, pyro technics and dramatic performances. Back in Germany, he had a successful career as an architect, universal engineer and writer. He designed a hospital, a waterworks system, a theatre, and houses. His cabinet of curiosities including models of scenic machinery was one of the most famous in Germany. A pious Lutheran, Furttenbach was at the same time an important cultural broker between Baroque Italy and Southern Germany. In three of his books, ''Architectura navalis'' 1629, ''Architectura universalis'' 1635 and ''[[Item:Q61|Architectura recreationis (Q61)]]'' 1640 he gathered the architectonical and technical knowledge of his time and wrote expositions on scenery and lighting for the theatre. |

The development of theatre architecture and technology has always been dependent on the sharing of knowledge and innovations, and in an age before telecommunications, the writings of Sabbatini and Furttenbach were critical to the advancement of theatre practice in their own time and since. | The development of theatre architecture and technology has always been dependent on the sharing of knowledge and innovations, and in an age before telecommunications, the writings of Sabbatini and Furttenbach were critical to the advancement of theatre practice in their own time and since. | ||

Revision as of 15:51, 11 February 2023

The books of Sabbatini and Furttenbach

Nicola Sabbatini (Q13) and Josef Furttenbach (Q60) documented theatre architecture and machinery as backstage practices during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Their writings were significant in preserving and spreading their knowledge of theatre architecture and technology across Europe and beyond.

Sabbatini was extremely influential for his pioneering and inventive designs of theatres, stage sets, lighting and stage machinery. Working in the court of the Dukes of Urbino, he was among the first designers of sophisticated machines which created realistic visual and sound effects such as the sea (the column wave machine), storms, thunder, lightnings, fire, hell, flying gods and clouds, and so on.

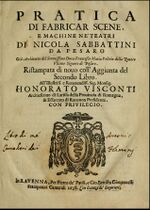

But the work Sabbatini is known for today is his treatise Pratica di fabricar scene e machine ne teatri (Q24), the first book of which was published in 1637. In the same year, Nicola Sabbatini took part in the project of the Teatro del Sole: Situated in former stables next to a palace, like the Florentine halls or the Teatro Farnese in Parma, or in a public barn, like the Teatro degli Intrepidi in Ferrara, the Teatro del Sole remodelled existing architecture for stage use. The treatise writes down and illustrates the scenographic practice of its time, giving clear guidelines on the construction of scenographic artefacts. Chapter by chapter the Pratica’s discourse is devoted to the architectural elements of the theatre's interior: hall, stage, tiers, orchestra, and the scenographies painted in perspective.

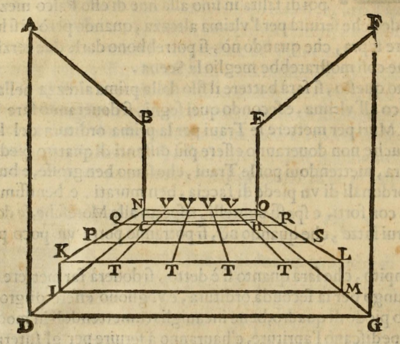

The first chapters focus on the construction of the stage, with a prior warning to check the structural stability of the existing building. It is important to point out that for Sabbatini the theatre is not built on a specifically created site, but reuses existing spaces. The stage is to be elevated, inclined with a gentle slope to facilitate performances with dancing. It is entirely built with wooden beams with enough space between the beams to allow for entrances. And it leaves the lower part open to accommodate the different stage mechanisms.

With the stage and sky in place, Sabbatini proceeds to position the point of view and the first wings. These not only completely organise the stage, but also the room, since the Prince’s viewpoint must coincide with the optimum point of the perspective, at the same height as the established horizon line, and in a central and forward position with respect to the room. Once the Prince’s point of view and the horizon line have been established, the urban scenes can be constructed in perspective using wooden frames with painted fabrics, and scene changes can be deployed to achieve the spectacle and illusion sought in the theatrical representation.

The audience is positioned in the room according to pre-established rules. A wooden railing nailed to the floor delimits the seats for the Prince’s court and his guard, who must be placed in the surrounding area. In the space immediately in front of the Prince, seated on chairs or benches, are the young women and immediately behind are the older women, followed by the men. Sabbatini does not concern himself with the chairs or benches, preferring to indicate how and in what order the spectators should sit. A self-supporting wooden tier is built around all the walls of the hall to accommodate the rest of the audience. Finally, the musicians can be located inside the hall, on a raised wooden balcony, decorated and hidden behind a lattice, or on a balcony inside the stage. Thus, the rules for building a theatre in an existing architectural space are set out.

Joseph Furttenbach the Elder was a German architect, mathematician, engineer and diarist. From 1607 to 1620 he stayed in Italy, where he did an apprenticeship as a merchant under the supervision of his uncles. Moreover, he studied engineering, military architecture and grew an interest in theatre and stage design while abroad as well as festivals, processions, pyro technics and dramatic performances. Back in Germany, he had a successful career as an architect, universal engineer and writer. He designed a hospital, a waterworks system, a theatre, and houses. His cabinet of curiosities including models of scenic machinery was one of the most famous in Germany. A pious Lutheran, Furttenbach was at the same time an important cultural broker between Baroque Italy and Southern Germany. In three of his books, Architectura navalis 1629, Architectura universalis 1635 and Architectura recreationis (Q61) 1640 he gathered the architectonical and technical knowledge of his time and wrote expositions on scenery and lighting for the theatre.

The development of theatre architecture and technology has always been dependent on the sharing of knowledge and innovations, and in an age before telecommunications, the writings of Sabbatini and Furttenbach were critical to the advancement of theatre practice in their own time and since.