Difference between revisions of "Colour Music"

(Created page with "''For centuries, people have dreamt of a kind of performance that uses light and colour in the way music uses sound. Many attempts have been made, including one by the theatre...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

''For centuries, people have dreamt of a kind of performance that uses light and colour in the way music uses sound. Many attempts have been made, including one by the theatre technologist Fred Bentham, but Colour Music has remained a marginal artform.'' | ''For centuries, people have dreamt of a kind of performance that uses light and colour in the way music uses sound. Many attempts have been made, including one by the theatre technologist Fred Bentham, but Colour Music has remained a marginal artform.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:IO2 J.07 01.jpg|300px|thumb|left|The original 1935 Light Console in the Strand demonstration theatre]] | ||

In the early 1930s, a young employee called [[Item:Q429|Fred Bentham]] (Q429) persuaded the directors of the Strand Electric and Engineering Company where he was working that they should invest a substantial amount of money in a new lighting control system: [[Item:Q30599|the Light Console]] (Q30599). At a time when lighting control in the UK and most of Europe was based on the mechanical operation of [[Item:Q3922|resistance dimmers]] (Q3922), Bentham’s system was quite unlike anything that had come before. It used technologies from cinema (the electric organ), the telephone industry (the cross-bar relay) and the Mansell magnetic clutch to remotely control a bank of dimmers, now motorised, from a control interface that would have been familiar to any cinema or church organist. With the Light Console, coloured light could be played as a musician plays music – what Bentham called Colour Music. | In the early 1930s, a young employee called [[Item:Q429|Fred Bentham]] (Q429) persuaded the directors of the Strand Electric and Engineering Company where he was working that they should invest a substantial amount of money in a new lighting control system: [[Item:Q30599|the Light Console]] (Q30599). At a time when lighting control in the UK and most of Europe was based on the mechanical operation of [[Item:Q3922|resistance dimmers]] (Q3922), Bentham’s system was quite unlike anything that had come before. It used technologies from cinema (the electric organ), the telephone industry (the cross-bar relay) and the Mansell magnetic clutch to remotely control a bank of dimmers, now motorised, from a control interface that would have been familiar to any cinema or church organist. With the Light Console, coloured light could be played as a musician plays music – what Bentham called Colour Music. | ||

| − | Bentham was not the first to have the idea for a performance of coloured light. In the 1720s the French Jesuit and mathematician Louis-Bertrand Castel experimented with a ''clavecin pour les yeux'' – a harpsichord for the eyes – the keys of which opened up shutters that let light shine through 60 small, coloured panes of glass. Around 1742, Castel went on to propose the ''clavecin oculaire'' (light organ) – an instrument to produce both sound and associated coloured light. The British painter Alexander Wallace Rimington spent many years developing an instrument that could project colours in harmony with music. He patented his ideas in 1894, and gave talks and demonstrations, accompanying music by Frédéric Chopin and Richard Wagner. He went on to publish a book in 1912, ''Colour Music: The Art of Mobile Colour'', in which he described the mechanism of his colour organ: a powerful arc-light of 13,000 candlepower produced white light that was passed through two prisms to provide a colour spectrum. These colours were then mixed and projected onto a screen, controlled by a keyboard and pedals. | + | Bentham was not the first to have the idea for a performance of coloured light. In the 1720s the French Jesuit and mathematician Louis-Bertrand Castel experimented with a ''clavecin pour les yeux'' – a harpsichord for the eyes – the keys of which opened up shutters that let light shine through 60 small, coloured panes of glass. Around 1742, Castel went on to propose the ''clavecin oculaire'' (light organ) – an instrument to produce both sound and associated coloured light. The British painter Alexander Wallace Rimington spent many years developing an instrument that could project colours in harmony with music. He patented his ideas in 1894, and gave talks and demonstrations, accompanying music by Frédéric Chopin and Richard Wagner. He went on to publish a book in 1912, ''Colour Music: The Art of Mobile Colour'', in which he described the mechanism of his colour organ: a powerful arc-light of 13,000 candlepower produced white light that was passed through two prisms to provide a colour spectrum. These colours were then mixed and projected onto a screen, controlled by a keyboard and pedals. |

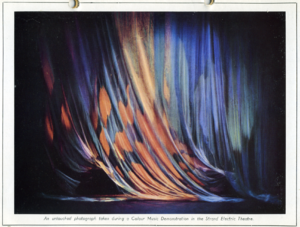

| + | [[File:IO2 J.07 02.png|300px|thumb|right|Bentham performed colour music by lighting drapes or abstract geometric forms, accompanying classical or jazz music]] | ||

| + | |||

Castel and Rimington are just two of the many people, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who promoted the idea that coloured light could be performed in a way equivalent to music, either on its own or combined with sound. While Bentham was not alone, he was perhaps the first to connect theatre stage lighting and colour music, through his development of the Light Console. While his personal passion was for colour music, to get the console made and to have an opportunity to operate it, he positioned it as a lighting control for theatre. The first to be built, in 1935, was installed in Strand’s demonstration studio in London, where Bentham could show it – along with Strand’s other stage lighting products – to potential customers. For most people in the theatre industry, however, the Light Console was a solution to a non-existent problem. Mechanical controls such as [[Item:Q3219|the Grand Master]] (Q3219) were seen as sufficient, cheaper and simpler to operate. | Castel and Rimington are just two of the many people, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who promoted the idea that coloured light could be performed in a way equivalent to music, either on its own or combined with sound. While Bentham was not alone, he was perhaps the first to connect theatre stage lighting and colour music, through his development of the Light Console. While his personal passion was for colour music, to get the console made and to have an opportunity to operate it, he positioned it as a lighting control for theatre. The first to be built, in 1935, was installed in Strand’s demonstration studio in London, where Bentham could show it – along with Strand’s other stage lighting products – to potential customers. For most people in the theatre industry, however, the Light Console was a solution to a non-existent problem. Mechanical controls such as [[Item:Q3219|the Grand Master]] (Q3219) were seen as sufficient, cheaper and simpler to operate. | ||

Latest revision as of 18:21, 18 February 2023

For centuries, people have dreamt of a kind of performance that uses light and colour in the way music uses sound. Many attempts have been made, including one by the theatre technologist Fred Bentham, but Colour Music has remained a marginal artform.

In the early 1930s, a young employee called Fred Bentham (Q429) persuaded the directors of the Strand Electric and Engineering Company where he was working that they should invest a substantial amount of money in a new lighting control system: the Light Console (Q30599). At a time when lighting control in the UK and most of Europe was based on the mechanical operation of resistance dimmers (Q3922), Bentham’s system was quite unlike anything that had come before. It used technologies from cinema (the electric organ), the telephone industry (the cross-bar relay) and the Mansell magnetic clutch to remotely control a bank of dimmers, now motorised, from a control interface that would have been familiar to any cinema or church organist. With the Light Console, coloured light could be played as a musician plays music – what Bentham called Colour Music.

Bentham was not the first to have the idea for a performance of coloured light. In the 1720s the French Jesuit and mathematician Louis-Bertrand Castel experimented with a clavecin pour les yeux – a harpsichord for the eyes – the keys of which opened up shutters that let light shine through 60 small, coloured panes of glass. Around 1742, Castel went on to propose the clavecin oculaire (light organ) – an instrument to produce both sound and associated coloured light. The British painter Alexander Wallace Rimington spent many years developing an instrument that could project colours in harmony with music. He patented his ideas in 1894, and gave talks and demonstrations, accompanying music by Frédéric Chopin and Richard Wagner. He went on to publish a book in 1912, Colour Music: The Art of Mobile Colour, in which he described the mechanism of his colour organ: a powerful arc-light of 13,000 candlepower produced white light that was passed through two prisms to provide a colour spectrum. These colours were then mixed and projected onto a screen, controlled by a keyboard and pedals.

Castel and Rimington are just two of the many people, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who promoted the idea that coloured light could be performed in a way equivalent to music, either on its own or combined with sound. While Bentham was not alone, he was perhaps the first to connect theatre stage lighting and colour music, through his development of the Light Console. While his personal passion was for colour music, to get the console made and to have an opportunity to operate it, he positioned it as a lighting control for theatre. The first to be built, in 1935, was installed in Strand’s demonstration studio in London, where Bentham could show it – along with Strand’s other stage lighting products – to potential customers. For most people in the theatre industry, however, the Light Console was a solution to a non-existent problem. Mechanical controls such as the Grand Master (Q3219) were seen as sufficient, cheaper and simpler to operate.

The Light Console had limited success commercially. Between 1935 and 1955 a total of 17 were made, installed in theatres in the UK and internationally. It particularly suited light entertainment shows, with rapid changes and music, and where speed of operation was more important that exact reproduction of timings and levels. For drama, there was a growing need for the reproducible control of many lights set to precise levels for each lighting state (C.07, C.08), and the Light Console did not meet that need. For theatre lighting, Bentham and his Light Console made a proposal – at a time when the lighting designer did not exist as a district professional role – that the lighting operator should be the person with creative responsibility for lighting. The industry had other ideas, and with the emergence of the lighting designer, the operation of lighting during the performance remained a matter of accurately reproducing the lighting that had been predetermined.

Bentham continued to perform colour music using the Light Console when he had the opportunity. He formed the Light Console Society, which met and gave recitals of colour music in the late 1930s; it had 101 members at one point. In 1939 Bentham designed a display for the London Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition, with a 23m high internally illuminated tower: the Kaleidakon. A Light Console and a conventional Compton cinema organ played the lighting and music. However, colour music – Bentham’s and that of a long list of other proponents – remained a marginal, specialist artform. Today, lighting for rock concerts fulfils something of the same role, and light is an established medium for visual artists, but the idea of light performance, as a distinct art, has yet to find its moment.