The hazards of the Elizabethan Pit[edit]

The theatre scene in Europe during the late 1500s can be defined as the period when all members of society were drawn to the theatre. There was a thirst for entertainment, but no infrastructure for the health and safety of actors and public.

Before the late 16th century, theatre had been generally reserved for members of the upper classes and royalty, often with actors being summoned to courts and estates to perform. But during the 1500s Europe developed a vibrant, commercial theatre scene that appealed to everyone. New theatres were built to meet this demand. Their ground-plan - like that of the Roman amphitheatres – wrapped the audience around a central stage, trying to fit in as many people as possible and optimising the viewpoint from many different angles. Buying a ticket didn’t have to cost a fortune. People of the lower classes could buy cheap tickets in the pit, an open standing space around the stage. People who could spend a little extra could buy a more comfortable seat on a bench in the gallery. In some cases, rich nobles and members of the upper class could pay to sit on a chair on the stage itself to observe the actors up close.

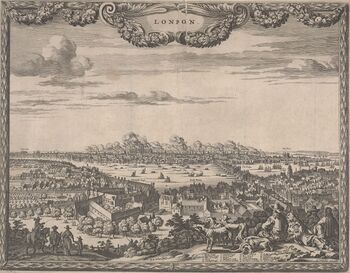

In London, public theatres weren’t allowed to be built in the city itself, as it was considered a possible health hazard where the plague and other diseases could manifest and spread. Large gatherings of people also attracted unseemly, vulgar behaviour, prostitution, and violence, which wasn’t wanted in the city centre. An entertainment district therefore developed south of the river Thames, beyond the control of the city authorities. The theatre district wasn’t a sanitary place: with no toilet facilities, people relieved themselves where they saw fit. Sewage was disposed in the river or buried. In the case of the Globe theatre, water from the nearby river Thames regularly flooded the lowest part of the building, creating a further hazard for the groundlings in the pit. This lack of hygiene is believed to have contributed to the spreading of the plague.

In the commercial theatres of the time, spectators’ bodies were pressed tightly together: at the Globe theatre there were 3,000 spectators in a space 45m in diameter. The replica of the Globe built in London in the late 1990s only welcomes 1570 people, with 700 standing in the pit – little more than half the capacity it had in the Renaissance era. Even allowing that people were smaller then than now, in the Elizabethan theatres they stood very closely together, leaving little room for movement, let alone enough room to prevent accidents in case of an emergency or tumult. The audiences in these public theatres weren’t always well behaved, by modern standards. People arrived late, left early, cheered and booed the actors and often tried to interact with them during the performance. Food or drink would be thrown on stage to express discontent. The 16th century theatre pit was the equivalent of the mosh pit in a modern-day music venue.

Disease and unruly behaviour were not the only hazards at the Globe theatre. When first built in 1599 the timber building was roofed with thatch, which in 1613 caught fire when a stage cannon set light to it. The theatre was destroyed, but it was rapidly rebuilt, reopening a year later - this time with a tiled roof. Sir Henry Wotton, an eyewitness of the fire, recorded the event in a letter dated July 2, 1613:

Now King Henry making a Masque at the Cardinal Wolsey's house, and certain cannons being shot off at his entry, some of the paper or other stuff, wherewith one of them was stopped, did light on the thatch, where being thought at first but idle smoak, and their eyes more attentive to the show, it kindled inwardly, and ran round like a train, consuming within less than an hour the whole house to the very ground. This was the fatal period of that virtuous fabrick, wherein yet nothing did perish but wood and straw, and a few forsaken cloaks; only one man had his breeches set on fire, that would perhaps have broyled him, if he had not by the benefit of a provident wit, put it out with a bottle of ale.

Another eyewitness, Mr. John Chamberaine, wrote in a letter of July 8, 1613 that the fire, ‘burn'd [the theatre] down to the ground in less than two hours, with a dwelling-house adjoyning; and it was a great marvaile and a fair grace of God that the people had so little harm, having but two narrow doors to get out.’ From these accounts we know that the initial smoke of the fire was ignored, as people believed it was from the canon, and that the theatre only had two exit doors to evacuate the audience of up to 3000. It is indeed remarkable that the injuries were not greater.

In the unregulated theatres of the Renaissance, fire, disease and violence were routine hazards, just as they were in the daily lives of the theatre-goers of the time.