The Asphaleia System

In the 19th century, the wooden theatres, lit by naked flames, frequently burned down, sometimes with great loss of life, and always at a financial cost. The Asphaleia system for building stages put safety first in all areas of theatre production.

The Viennese engineering Asphaleia Society for the Production of Contemporary Theatre (Gesellschaft zur Herstellung zeitgemässer Theater ‘Asphaleia’) developed a comprehensive theatre-building concept towards the end of the 19th century (Q19107). Safety – the Greek word asphaleia - was the top priority, but aesthetic criteria such as sight lines and completely electric lighting were also included. The stage machinery system laid the foundation for modernity with hydraulics replacing manual operation.

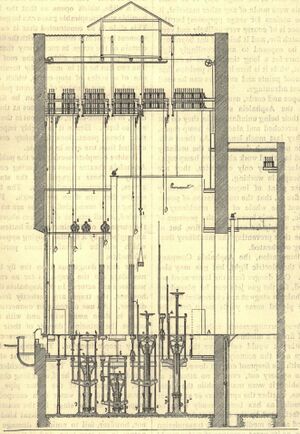

The Asphaleia system had been devised by the engineer Gwinner and the decorative painter of the court theatres Johann Kautsky, both from Vienna. The system was a response to the Ringtheater fire (Q696), which triggered strict safety regulations in theatre construction; it replaced the hitherto customary wood as a building material with iron, and brought a number of improvements in stage machinery. The Asphaleia Society designed fireproof stage machinery with a steel structure that was set in motion by water hydraulics. This ingenious design was first realised in Budapest in 1884 on the stage of the opera house planned by Miklós Ybl and then built in only ten months (Q7696).

The originator of the machinery of the Asphaleia system was the Viennese engineer Robert Gwinner. His designs for stage equipment were used at many other theatres, including at the Landestheater in Prague, the Raimundtheater in Vienna, the newly built theatres in Halle an der Saale, Göggingen near Augsburg, the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London, and the Great theatre in Chicago. In 1882, Gwinner and Co. were granted the patent of a ‘theatre machinery which provides perfect mobility of the stage components with perfect safety in every respect’.

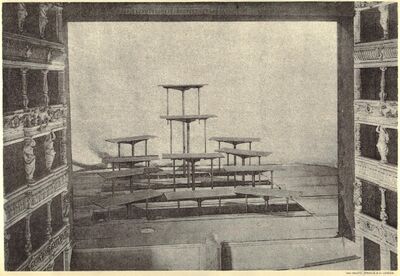

However, it was not only safety aspects that inspired the Aspahleia Society’s new theatre construction concept. Rather, they saw the fire risk in the context of an urgently needed reform of the theatre, which they considered not only unsafe in its traditional form, but also aesthetically unsuitable to meet contemporary requirements. The previous backdrop/scenery system was not able to create a total illusion, but at best to suggest a situation. The stage set had to make the step from the flat to the plastic, from the two-dimensional to the three-dimensional. The Asphaleia Society therefore called for a complete, state-of-the-art system change in the theatre. The focus was on the stage system, especially the stage machinery, where they saw the greatest risk of fire breaking out. At that time, stages were built of easily combustible wood, and were to be replaced by steel.

The city theatre building in Halle in Germany (Q8074) replaced a wooden predecessor in 1883-1886. By the power of hydraulic machines, five segments of the stage could be extended as platforms, lowered, set in an inclined position and even set in a rocking motion. A semi-circular cyclorama took the place of the earlier wings and backdrops. Hydraulics also powered the flying machinery. The hydraulic system replaced completely the manual operating of the stage, which was revolutionary at that time. A control system allowed the operation by only one person. By this, they were convinced, the number of badly qualified stagehands could also be reduced and with this, the risk of accidents. Therefore, the Aspahleia system also demanded the introduction and improvement of the training of theatre machinists.

The safety installation included a circular iron pipe all around the auditorium and the stage tower. From there, vertical tubes went to all floors to transport water from the cellar to all parts of the building in case of fire. Electricity was generated by two steam engines of 60hp in their own cellar, so that the complete lighting could be realised, greatly reducing the risk of fire compared to the previous gas lighting. There was also a second system of emergency lighting.

The Asphaleia system began with a concern for safety, and many of the safety innovations it introduced are still to be seen in theatres: steel construction of the stage structure and flying systems; secondary lighting in the event of power failure of the main system; drencher systems to spray water in large volumes in the event of fire. Powered machinery has reduced the need for manual handling and allowed for safety mechanisms to be built in. But the Asphaleia system’s comprehensive approach to all aspects of theatre production also ushered in a new era of stage design, ended the 400-year reign of the wooden stage and laid the foundation for today’s mechanised stage systems. The illusions of the earlier stages were replaced by spatial stage design, which opened up new artistic possibilities for modern theatre with electric stage lighting. Asphaleia’s patented stage system with its ingenious technical solutions was later installed in theatres all over the world (A.06). Every stage technology of today is a further development of the Asphaleia system.