Sound on Cue

In the 1950s, the new technologies of the panatrope and, later, the tape recorder, allowed pre-recorded sound to be replayed on cue, so establishing the creative potential for sound as a central dramaturgical element of performance.

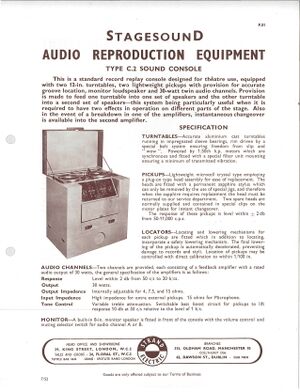

The 1953 catalogue of the Strand Electric Company (Q64), based in London, featured the ‘Type C.2 Sound Console’ – a large cabinet equipped with two 12-inch turntables, able to replay sound effects recorded on phonograph records. The unit had two built-in amplifiers each rated at 30W, ready to connect to loudspeakers front of house or on stage, as well as a sophisticated system for lowering the stylus at the correct point on the record to start the sound precisely on cue. A speaker allowed the operator to monitor the sound before fading it up on stage, and the two turntables meant that two effects could be played simultaneously, or could be cross-faded from one effect to another. The C.2 Sound Console was the state of the art for theatre sound effects reproduction in 1953, offering the fundamental features required for this purpose: multiple sources, accurate cuing, control of volume, and monitoring independent of the stage output.

The Strand C.2 was not the first such device. In the late 1930s, a company called Simon Sound created a similar machine with two turntables and an amplifier, specifically to play theatre sound effects. These became known as panatropes, borrowing the name from ‘the first purely electrical reproducing musical instrument’, launched in 1925 in the USA by the Brunswick Company, though the Brunswick machine was intended for domestic use and only had one turntable.

After the Second World War, Jack Bishop was running an electronics shop in London, and supplying recorded effects discs for theatre productions. To meet demand, he obtained some Simon Sound panatropes, but then developed his own, improved version (Q23450). The most important innovation was the cuebar – a metal rod with a movable collar that positioned the pick-up head over the disc, so that when it was lowered it landed at exactly the right spot on the record. To avoid a click as the stylus landed, the operator would only raise the volume once the stylus had landed in the groove. The cuebar could be swapped for each cue, allowing several cuebars to be set in advance, one for each cue, ensuring accurate replay at each performance. Bishop hired the panatrope with a pair of loudspeakers for £4 a week, plus sixpence for each cuebar. Bishop’s panatrope, and its Strand equivalent, became a standard piece of equipment in theatres in the 1950s. More complex shows would use more than one machine, with several operators required for busy effects sequences. Other companies began to hire out panatropes, such as RG Jones and Stagesound, and the UK theatre sound industry was created.

While the panatrope brought together the key requirements for sound effects replay, it had several limitations. Recording the sound effects discs was a specialist job, so theatres would either use ‘off the shelf’ ready-made effects, or commission discs for the production. The maximum length of a sound effect was also limited, and the discs wore out and had to be replaced every few weeks of the show’s run. These problems were solved with the development of the reel-to-reel tape recorder. The technology to record sound onto tape – initially a band of steel, but later a plastic tape with a magnetic coating – had been invented and progressively developed in the 1920s and 1930s. In the late 1950s, Stagesound adapted the technology for theatre use, launching its Cue Tape machine, which incorporated a device to stop the tape automatically when it reached a piece of metal tape edited into the recording tape. For theatre producers, the tape recorder was advantageous: it cost the same to hire as a panatrope, but there was no need to replace the discs every few weeks. Also, the tape recorder operated at the press of a button, and didn’t require a skilled ‘pan operator’.

However, the move from discs to tape was not welcomed by everyone. For some young directors interested in the dramaturgical possibilities of sound, tape was the less flexible medium, requiring everything to be recorded on the tape in the order it would be used in performance. With a skilled pan operator, a director could try out different sequences and combinations of sound by having a collection of discs in rehearsal, and swapping them as required. This was particularly helpful as the overall effect could only be judged once the sounds were being played in the acoustics of the actual theatre, rather than in the rehearsal room; the ability to experiment offered by discs only re-emerged with the advent of the digital sampler, with its instant-access memory. For some productions, the sound would initially be played from discs until everything was settled after the first few performances, and then transferred to tape for the remainder of the run.

The panatrope, and later the tape recorder, brought the possibility of pre-recorded sound, replayed to selected speakers in the theatre space at a controlled level and on cue, thus opening up new possibilities for sound as a component of theatre performance. Previously, sound was limited to what could be created acoustically live during the performance, using musical instruments, machines or the human voice. Now, any sound that could be recorded was available, greatly increasing the possibilities of sound. While the early equipment still had significant limitations, it pointed the way, and – as a side effect – it triggered the creation of a new professional role. Directors needed someone with both the technical expertise and creative understanding to pre-plan the dramaturgical use of sound: the sound designer.