The ‘natural’ state and how to control it[edit]

Although the theatres of Antiquity were illuminated by daylight, the Greeks and Romans had various strategies for making the best use of the available light to support the performance.

The earliest known Greek theatre is the Theatre of Dionysus (Q7829), on the southern side of the Acropolis cliff in Athens, dating from around the 6th century BCE. At first, theatres were open spaces that allowed for dancing and rites. Over time, masonry seats were added in a semi-circle around the area for the chorus (the orchestra). The theatre was extended in several stages to eventually accommodate an audience of around 17,000 people. It was mainly used during the festival held at the end of March and April, initially to celebrate the year’s harvest and the end of winter, and later as a celebration of the god of wine, Dionysus. The festival lasted about a week and was a competition in which several plays by different playwrights were performed. The first day was devoted to processions, and on the next the playwrights announced the plays and judges were appointed. For the next four days, four to five dramas were performed each day, so it was necessary to start early in the morning and finish well into the evening. The changing light during the day was therefore a major part of the experience.

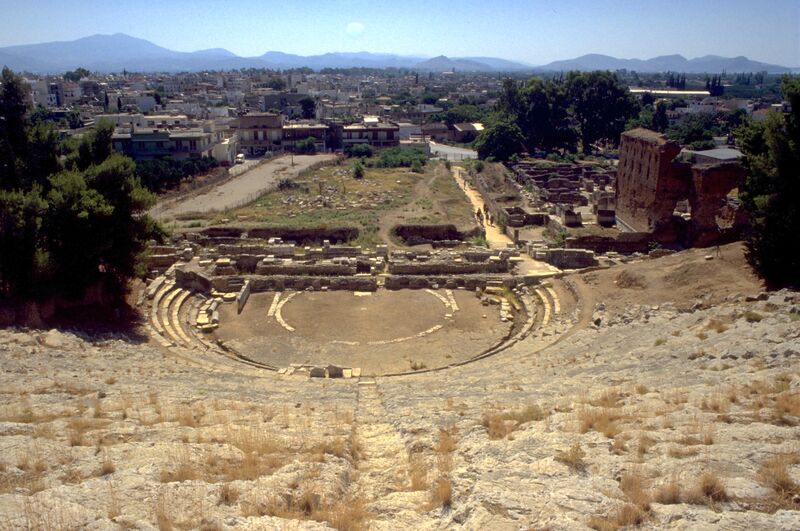

During the early morning hours, the dawn light allowed for some activity in the surrounding area. Greek theatres were built on hillsides outside the city, with the site chosen both to give the necessary shape to the bank of seating, but also for the view across the valley, which acted as a backdrop to the stage. There are examples of plays where the opening text talks about what is happening in a foreign country, so it was possible to light a large fire on this hillside to serve as a sign of activity in a foreign land. Later in the performance day it was necessary to use other signs, for example to show it was night-time in the play. One way was to have an actor come in with a lit torch, signifying night. Another way was to hang a black or dark drape in the doorway of the skene (the building at the back of the stage). This served as a sign for night which would have been understood by the audience.

It is widely believed that the Greeks built theatres in such a way that the sun's migration across the sky could be exploited during the course of the day. It is true that many theatres were oriented so that the theatre building was oriented in an east-west direction. However, it is not so consistent as regards the audience seating, which was sometimes built on the southern slope of the mountain and sometimes on its northern slope. There have also been ideas that the Greeks used mirrors to throw light onto the orchestra and the skene. However, there are no definite sources to confirm this. A likely origin for this idea could be what is usually called ‘Archimedes’ mirrors’, a proposed weapon against warships which is attributed to Archimedes. According to this idea, many mirrors aimed at a warship could set it on fire if the reflection of the sun were concentrated in a small focal point. However, there are no sources to support that this could ever be done. The Greeks never made mirrors larger than hand mirrors, and these were a highly polished bronze surface, not the silvered glass of modern mirrors. In the theatre, on the other hand, mirrors could have been used to cast solar reflections – ‘sun cats’ – onto the stage as a one-off effect rather than to illuminate the stage and actors.

The Romans also sought to control the conditions that prevailed when performances were given outdoors in their theatres and amphitheatres. The major difference in construction between the Greek and Roman venues was that the Greek venues were located on the slope of a mountain or hill, while the Romans constructed buildings on flat ground in the centre of the city. The Greek theatre was open and therefore allowed the wind to easily blow through the venue and thus cool the audience. At the same time, it was very difficult to put up sunshades for the audience. In the Roman theatre and amphitheatre, the situation was the reverse. It was much more difficult for the wind to blow through the building, but the Romans were able to provide their theatre buildings and amphitheatres with sun protection sails (Velarium). These sunshades were supported by ropes stretched between masts along the perimeter wall of the building. These masts have long since disappeared, but their attachment points are still visible today, for example at the Colosseum in Rome (Q615).

Greek and Roman theatres did not seek to close themselves off from the outside environment: the audience was always aware of the natural light, temperature, wind and weather. Rather, they used various techniques to manage that environment, and to signal when the actual environment differed from that in the fictional world of the play.