The Price of Entry

Commercialising theatre

The late 16th and early 17th century saw a great growth in the public demand for theatre in Spain and England. New venues were needed, and new methods to run theatres as commercial enterprises, without the support of a monarch or wealthy patron.

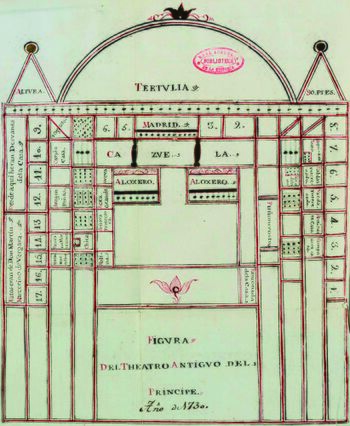

The Golden Age is the name given to a period in which Spanish literature flourished, from the end of the 15th century to the late 17th century. Inseparable from the development of dramatic literature were the physical conditions that made the existence of theatre possible: the venues and ensembles, the organisation of audiences and the infrastructure as a whole. However, before the mid 16th century the concept of a building dedicated to the performance of theatre did not exist in Spain. The first public theatres were the Corral de Comedias – theatres built in the form of courtyards. The first of these was the Corral de la Cruz, Madrid, built in 1579 (Q13175), then the Corral del Príncipe in Madrid in 1583 (Q13175). Others followed.

A decree by King Philip II in 1565 established in Madrid brotherhoods (like guilds) to build and run the corrals, as a way to regulate the immoral content of theatre. Profits from entrance fees, introduced in a structured way for the first time, were used to fund hospitals. As demand grew, the brotherhoods created new corrals.

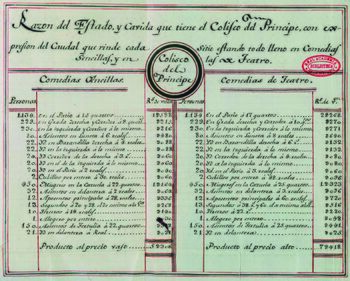

Over time, the income was found insufficient to support the hospitals, and in 1623 reforms made the brotherhoods responsible for protecting the comedias (meaning all types of theatre: comedy, tragedy and satire) and for operating a system of censorship. Income from entry fees was still central, however; by 1630 the Corral del Príncipe had increased its seating capacity from 1000 to 2000 spectators since the first opening.

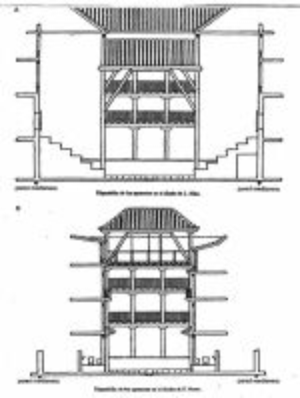

In the corrals, the audience was divided by social class and gender: the men of the common public watched the spectacle standing in the centre of the courtyard, while the side balconies had rooms for the nobility. Opposite the stage the upper floor housed the clergy and the city’s notables. Below this was the women’s cazuela, immediately adjacent to the entrance. A spectator who wanted to reserve a seat had to pay a triple ticket: for the company of actors, for the landlord of the corral and for the seat reservation.

The Red Lion (Q30603) was an Elizabethan playhouse located in Whitechapel, London. It was built in 1567 for John Brayne, and is the first known purpose-built playhouse in London since Roman times. It was designed to serve the many touring theatre companies that played in the courtyards of inns. Its existence was short-lived, however, as the theatre seems not to have survived after the summer season of 1567. The Red Lion was outside the City of London, in open farmland, and unattractive to travel to in the winter.

Brayne and his brother-in-law, the actor-manager James Burbage, went on to build a theatre known simply as The Theatre (Q10092). Unlike the Red Lion, The Theatre accepted long-term residencies, with theatre companies being based there: a radically new form of theatrical engagement. It was expensive to build, and as well as borrowing money, Brayne and Burbage put on performances while the theatre was still under construction to fund it. Once open, it was commercially successful; spectators could pay one penny to stand in the open area in front of the stage, or two pence to stand in the raised and covered galleries. For three pence, they could have a stool to sit on. Wealthier patrons could pay for a private compartment in the galleries.

Brayne and Burbage did not own the site of The Theatre, and when the lease expired they decided to reuse the timber to build a bigger theatre with more capacity – the Globe (1599, Q7846). The cost of construction and lease was divided between the previous founders Cuthberd and Richard Burbage, and William Shakespeare. By this time the Rose (1587, Q12550) and Swan (1596, Q8428) theatres had also opened.

The Globe was larger than the earlier theatres, with a capacity of about 3,000 spectators. Following the multi-level model of The Theatre again allowed the division of the audience by wealth and social status. Nevertheless, all the audience came in through a single entrance, ensuring no-one could enter without paying.

In Madrid and in London, the popular demand for theatre in the late 16th and early 17th centuries led to the creation of new venues, and new organisational structures. Money was raised by borrowing, with lenders gaining a share in future profits. State control continued in various ways, but entrance fees were the source of revenue – maximised by offering the wealthier audience members better facilities for a higher price, while segregating them from other parts of society. This model of commercial operation, with elements of state intervention and regulation, has continued to the present day.