Industrial Revolution

Underlying the theatrical changes of the 19th century were the social upheavals following the French Revolution. Across Europe the middle class took over or built new theatres, effecting changes to repertoire, style and design, as well as machinery.

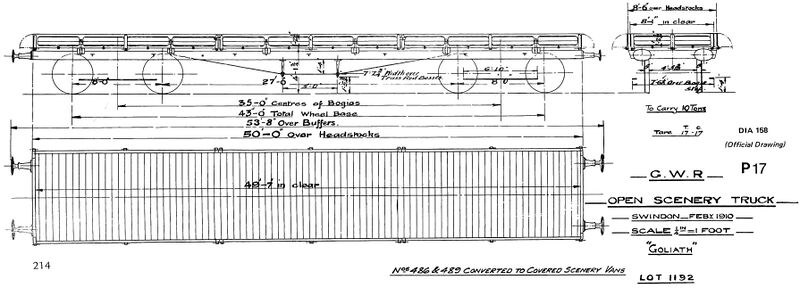

Throughout the 19th century, cities exploded in size, as industrial centres attracted labour to their factories and mills. The working-class suburbs of cities and the industrial towns created their own demand for entertainment, which led to the construction of large theatres. The pattern of theatre was disrupted: in England, for example, productions were mounted in London and sent on tour, facilitated by the growth of the railways, which could rapidly and cheaply transport not only a company of actors, but an entire production with scenery, costumes and props. The railway companies even built special trucks to transport scenery. The old provincial stock companies folded and theatres became touring venues rather than producing houses. The change in status from enterprise to industry gave rise to the commercial theatre systems and the exchange of productions further extended the possibilities of profitable exploitation. Touring companies were led by actor-managers, such as Henry Irving (Q257), who formed their own companies and controlled the actors, the production, and the financing, as well as staring in the productions. The most successful of these were enormously popular, gathering huge audiences.

National theatres were founded to give expression to the views and values of the middle class. In western Europe a different pattern of development emerged, varying considerably in each country but having the unified features of a demand for ‘realism’ on the stage, which meant a faithful reflection of the life-style and domestic surroundings of the rising class in both its tragic and its comic aspects. Those in revolt founded so-called independent theatres to present a more critical or scientific view of the workings of society or so-called art theatres to rise above vulgar materialism with the establishment of aesthetic standards. Independent theatres took the Meiningen Ensemble as their model, sometimes only to a closed membership, to avoid censorship. The art theatres looked to Wagner for inspiration.

The new theatre demanded ‘truthfulness’ not only in the writing but also in the acting and stage setting. The actors were expected to ignore the audience and to behave and speak as though they were at home; from this style of acting arose the concept of the ‘fourth wall’ separating the stage from the audience. Behind this ‘wall’ – invisible to the audience, opaque to the actors – the environment portrayed was to be as authentic as possible. If an attack on the audience were to be mounted effectively, however, the separation of stage and auditorium had to be diminished. Attempts were later made either to contain stage and auditorium in a single unified spatial area or to adapt existing spaces in order to break through the barrier imposed by the proscenium arch.

With both ideological aims and theatrical tastes in mind, members of the German middle-class theatre audience formed an organisation called the Freie Volksbühne in 1890 for the purpose of buying blocks of tickets and commissioning performances and even productions for its membership, which included a large working-class element. During the 1890s in France, a similar program of democratisation was attempted by Le Théâtre du Peuple, inspiring similar movements in other countries. In England the works of Ibsen aroused great interest and attracted the attention of the censors, as with the work of George Bernard Shaw.

Beyond the development of stage lighting and techniques, from the 1880s electricity provided the solution to many of the problems that were arising with respect to scene changing (C.06). The demand for rapid changes of cumbersome naturalistic sets coincided with demands for a dematerialised stage that could flow smoothly from one symbolic vision to another. In addition, those seeking to ‘retheatricalise the theatre’ wanted an open stage on which scene changes could be accomplished simply and rapidly. New inventions and instrumentation made practical many of the theoretician’s ideas, and these were adapted by designers, directors, and stage engineers on both sides of the Atlantic, with the greatest centre of innovation being Germany.

In 1896 Karl Lautenschläger introduced a revolving stage at the Residenz Theater in Munich (Q13019). Elevator stages permitted new settings to be assembled below stage and then lifted to the height of the stage as the existing setting was withdrawn to the rear and dropped to below-stage level. Slip stages allowed large trucks to be stored in the wings or rear stage and then slid into view. New systems for flying were developed. Hydraulic stages made it possible to raise sections of the stage, tilt them or even rock them to simulate, for example, the motion of a ship. All of these mechanisms required larger backstage facilities, higher flying towers, greater depth and width of stages, and increased understage space.

The 19th century was the peak of the industrial revolution, radically changing not only technologies, but the whole of society across Europe. The theatre took on new roles, used new methods to produce work, organised itself in new ways, and made performances that were innovative in content and form.