Infinite Skies

The dome and the plaster or cloth cyclorama are used to create a sense of infinite space within the confines of the stage, lit to evoke the sky, to express the dramatic mood, or used as a projection surface.

In 1922, Kenneth Macgowan (Q29856) wrote, The dome, or some variety of it, is found in practically every German theater. Linnebach estimates that there are twenty true Kuppelhorizonts, cupping the whole stage with a curving dome; ten permanent Rundhorizonts, plaster cycloramas curving like a great semi-circular wall around the stage; and thirty canvas cycloramas which are quite as large as the Rundhorizont, and some of which are so hung as to make a most convenient and efficient substitute for either variety of plaster sky. (Q29855: 71) This commitment – technical, financial, and artistic – to the representation of sky, and to providing an enveloping environment of light, was a distinctive feature of German stages in the first decades of the twentieth century, and to a lesser extent elsewhere in Europe.

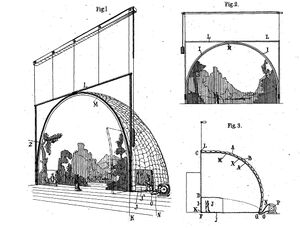

At the start of the twentieth century the Spanish polymath Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo (Q231) invented a sky half-dome to surround the stage, produced by exhausting air from between two curved surfaces of silk, the outer one fastened to a folding frame of steel (Q332). The light of arc lamps, coloured by reflecting it off strips of silk, created a dynamic space of colour and light. Although Fortuny’s system was hampered by technical problems, the dome, and the simpler and more flexible plaster or cloth cyclorama, became an established feature of many theatres.

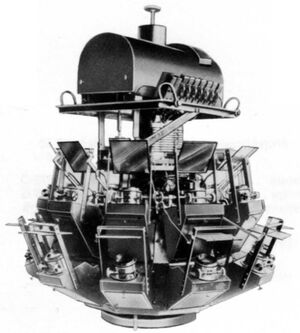

These domes and cycloramas required new methods to light them. In the 1920s, Hans Schwabe and Max Hasait developed a 7-colour mixing system using carefully selected colours that when mixed produced white, but which in various combinations could create a complete palette of colours (Q23493). Specially designed lighting fixtures used curved reflectors to give an even distribution, with glass filters creating the required colour. Companies such as Reiche & Vogel devised elaborate cloud machines that rotated slowly, projecting the image of clouds moving across the sky, through multiple lenses and mirrors. Simpler versions used a rotating disc in a single projector to create moving clouds.

The aim was not always to recreate a naturalistic sky. Domes and cycloramas became surfaces for the dynamic use of abstract colour; by lighting from different directions (above, below, and each side) blends of colour could be achieved. In a large theatre, with enough space between the lit area of the stage and the cyclorama, the effect of an empty void could be created by not lighting the cyclorama at all. These effects were used expressionistically, to underscore in light and darkness the emotional narrative of the drama.

Domes and cycloramas also became surfaces for projection. In 1917 Adolf Linnebach (Q419) developed a simple but effective system for projecting an image without lenses, comprising a single, powerful light source and a large glass slide (Q639). The required image was painted on the glass with translucent paints, and opaque cut-outs created shadows within the scene. Although the image was not optically sharp, the system made highly impressionistic effects that could be combined with lighting. Later, projectors were developed by companies such as Pani, with lens systems that produced sharply focused images. Slides could be created by the painting method, or photographically. These projectors became standard equipment in large theatres and opera houses, until replaced by today’s digital video projectors.

Equipment and techniques developed for the theatre were adopted in other fields. Cinemas of the 1920s and 1930s installed lighting and projection equipment to fill the auditorium with atmospheric effects of sky and clouds between the screening of films. The ‘wrap around’ cyclorama, together with its lighting equipment, became a standard feature of most television studios. Domes are now used in planetariums to give spectators the experience of the night sky, while video projection is used in art galleries to create immersive experiences, with images projected on every surface. In the ‘fulldome’ concept, films shot with 360-degree cameras are projected onto the inside of a dome containing the audience.

In theatre, changing fashions in stage design mean the permanent domes and plaster cycloramas have mostly been removed. Curved, cloth cycloramas remain, but flat, two-dimensional cycs are more common, with their associated equipment to light them from above and below. New lighting technologies have brought greater flexibility, however, with LED cyc lights offering a range of colours never seen previously. As Macgowan wrote in 1922, thus it is in some scenes a pale neutral wall, in some a curious violet emptiness, in others a faintly salmon background, in still another a yellow light against which figures move in tiny silhouettes … the dome becomes a misty void in one of the dream-scenes; and then upon this void move vast, mysterious shadows in circling procession. (Q29855: 72)