Naked Trashiness

The introduction of electric lighting into theatres had a profound effect on how light could be controlled and used on stage. Eventually, through many interconnecting developments, electricity unlocked lighting’s expressive potential.

In 1908 the English actress Ellen Terry wrote in her autobiography, Until electricity has been greatly improved and developed, it can never be to the stage what gas was. The thick softness of gaslight, with the lovely specks and motes in it, so like natural light, gave illusion to many a scene which is now revealed in all its naked trashiness by electricity. (Q29976: 172-3)

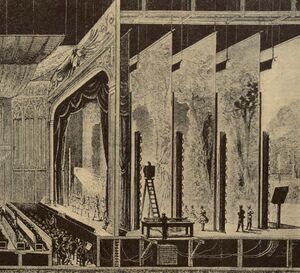

Terry was not alone in her criticisms of electric lighting when it first became widespread in theatres in the 1880s and 1890s. There were widespread concerns that it was cold in appearance, and too revealing of the scene-painting techniques of the time, making the scenery look dull and lifeless. Nevertheless, electric lighting was rapidly adopted in theatres. Theatre managers were not motivated by aesthetics so much as the greatly reduced risk of fire, which had been a major hazard previously. In some regions, electric lighting became a legal requirement in theatres for safety reasons, for example in Vienna following the Ringtheatre fire of 1881 (Q696). Electric lighting also eliminated the excessive heat and noxious fumes of gas.

The first electric light to be used in theatres was the carbon arc lamp, invented at the start of the 19th century by Humphry Davy (Q29974). However, while arc lamps produced a powerful output, they had two disadvantages that limited their use. They required an electricity supply, which was not readily available until the late 19th century. They also needed constant adjustment, and so an operator to be with each lamp, limiting where they could be positioned in the theatre. The limelight, although invented after the arc lamp, was preferred through much of the 19th century, since its gas fuel could be kept and transported in leather bags (Q176). In both cases, the intense, directional light was mainly reserved for special effects and ‘key’ lighting, such as representing sun or moonlight, rather than for general stage lighting.

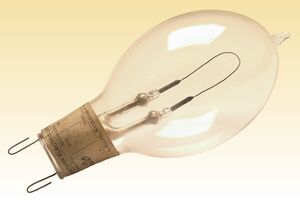

Fully electric lighting in theatres did not arrive until the development of the incandescent light bulb (Q3120), in which a thin filament is heated to white heat by passing electricity through it. Although experiments had been made since the mid 18th century, there was great difficulty in finding a filament material that would not melt, or burn up in the air. The first practical lamps appeared at the start of the 1880s, using a carbon filament in a glass envelope from which the air had been evacuated. When the Savoy Theatre in London opened in 1881, it was the first theatre, and the first public building in the world, to be lit entirely by electricity (Q8188). Attempts to create a brighter and more efficient lamp using different filament materials eventually led to the tungsten lamp – tungsten having the highest melting point of any metal. By 1910, the tungsten filament in an evacuated glass envelope was the standard.

Early electric lamps were a similar brightness to gas burners, and were installed in the same locations, although being able to operate at any angle made it easier to direct light onto the stage from overhead, finally eliminating the need for footlights. Once the tungsten filament was established, attention turned to creating brighter, more powerful lamps. The power of each lamp rose from around 40W to as much as 3000W by the early 1920s. More powerful lamps meant that a single luminaire could have an impact, rather than relying on large quantities of small lamps in rows to achieve the required light levels (Q29977).

Reflectors and lenses gave control of the beam, although these systems demanded bright, compact filaments to provide as close to a ‘point source’ as possible. At first, the position of the lamp in the optical path needed to be laboriously adjusted to give the maximum light output and an even beam, but the invention of the pre-focus cap in 1951 meant that lamps were interchangeable without the need for individual adjustment (Q29978). Later innovations increased efficiency, power (up to 10,000W) and lamp life, but by the mid 20th century the key lamp and luminaire technologies were in place to deliver light on stage in the way we still do today: a large number of high-brightness spotlights, each giving precise control of intensity, direction, colour and distribution of light, building up the scene like a painting, brush-stroke by brush-stroke.

In 1922, Kenneth Macgowan wrote, In the ‘eighties and ‘nineties, when electricity came into the theatre to take the place of gas, light was only illumination. By the first decade of the twentieth century it had become atmosphere. Today it is taking the place of setting in many Continental theaters. Tomorrow it may be part of drama itself. (Q29855: 68)

One hundred years later, lighting is indeed a dramaturgical force in theatre performance, its potential unlocked by the coming of electricity.