Rejecting Naturalism

Early 20th century Expressionism sought to move away from the Naturalism of the late 19th century that attempted a facsimile of real life. Instead, Expressionism used light and simplified, abstract scenic forms to invoke strong feelings in audiences.

Expressionist theatre employed very different scenographies compared to the theatrical movements that came before it like Naturalism and Romanticism. Set pieces and props were typically used sparingly with much more emphasis on creating striking sound and light. The scenery was typically very symbolic and was a purposeful exaggeration or understatement of the setting, aimed at invoking intense emotions and uncovering the overlooked failure of societal systems. Commonly, Expressionism shifted emphasis from the text to aspects of the physical performance and highlighted the director’s role in creating a vehicle to deliver theirs and the playwright’s thoughts to the audience, as in the productions and writings of Edward Gordon Craig (Q325).

Gordon Craig worked as an actor, director and scenic designer, building elaborately symbolic sets. He asserted that the director was ‘the true artist of the theatre’ and, controversially, suggested viewing actors as no more important than marionettes. He was also the editor and chief writer for the first international theatre magazine, The Mask (Q30609).

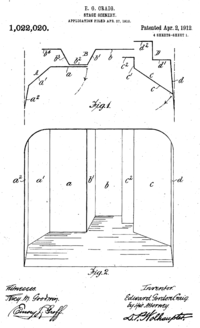

Craig concentrated on keeping his designs simple, so as to set-off the movements of the actors and of light, and introduced the idea of a ‘unified stage picture’ that covered all the elements of design, which he described in one of his most famous works, the essay The Art of the Theatre (Q704). Craig’s idea of using neutral, mobile, non-representational screens as a staging device is probably his most famous scenographic concept. In 1910 Craig filed a patent which described in considerable technical detail a system of hinged and fixed flats that could be quickly arranged to cater for both internal and external scenes. Craig’s second innovation was in stage lighting. Doing away with traditional footlights, Craig lit the stage only from above, placing lights in the ceiling of the theatre. Colour and light also became central to Craig’s stage conceptualisations. The third remarkable aspect of Craig’s experiments in theatrical form were his attempts to integrate design elements with his work with actors. He promoted a theatre focused on the craft of the director – a theatre where action, words, colour and rhythm combine in dynamic dramatic form.

Craig corresponded with Stanislavski, Appia, Duse, Reinhardt, Copeau and Dalcroze, among others. He was editor and director of three magazines devoted to the stage: The Page (1898-1901), The Mask (1908-1915, 1918-1919, 1923-1932), and The Marionette (1918). In these he wrote many studies, articles and notes under seventy different pseudonyms. However, Craig was not a rationalist theoretician, but a visionary artist; for him, writing was the means of fighting and convincing.

The new scenic art promulgated by Adolphe Appia and Edward Gordon Craig has embodied the changes that have established the basic principles of contemporary stage direction and design. Craig synthesised action, word, dance and gesture in a total show. He abstracted the literal to achieve a simplicity that allows light to highlight the space, austere and timeless. Until his intervention, the theatre was the support of the text. Thanks to Craig and Appia’s proposals, the scenery becomes a laboratory combining screens, prisms, stairs and segments to obtain the maximum expression from the minimum number of forms, on which the light falls until they are endowed with the desired expression.

In The Art of Theatre Craig establishes a revision and renewal of theatre in opposition to the naturalism that prevailed in theatre at that time. To move away from realism on stage, he proposes the actor as a creator of signs and forms that reflect ideas that reach the viewer, making him a participant in what happens. The actor, therefore, must become an inanimate figure who builds the character, leaving aside naturalism, going one step further. The scenery is understood as a space for the action of the character. That is why Craig insisted on the use of simplified architectures and gave the main function to the stage floor.

He created environments, evoked and dematerialised objects to turn them into ideas and symbols. For Craig, lighting and colour were the main sources of evocation and spatial expression. His work has influenced subsequent theatre fundamentally in the way in which scenery, costumes and lighting merge into a unified conception of total scenography, central to the theatrical experience.