Painting with Light

In the inter-war period, increasingly powerful electric lamps enabled the first spotlights, creating focused beams of light. A new lighting style emerged, based on large numbers of sources, each lighting a small portion of the stage with precision.

In 1967, the lighting designer Richard Pilbrow wrote an article titled ‘A Multi-lantern Complexity - Why?’ (Q30013). In it, he described in detail an approach to lighting the stage enabled by developments in lighting equipment that had taken place during the interwar period, and further refined in the 1950s and 1960s. The basis of this approach was the precise control of the distribution of light in space, to an extent never previously possible, and which is the foundation of stage lighting today.

When electric lighting became commercially available towards the end of the 19th century, the lamps were similar in brightness to the gas flames they replaced. Lamps therefore continued to be located in the same numbers and places to the previous lighting: overhead, wings, and footlights. Carbon arc lamps (Q232) continued in their role of providing intense, single sources for effects such as sunlight and moonlight, but the practical limitation of needing the constant attention of an operator limited their use. Incandescent lamps (Q3120) improved in the 1910s and 1920s, becoming bright enough to be used as single sources, their light output gathered by a reflector behind the lamp, and a lens in front of it, concentrating the beam.

The first such spotlights used a single, plano-convex lens, in an optical arrangement still known as the ‘PC’ or focus spot (Q3198). They could be used from the wings and from overhead, and even from front of house, although auditoriums rarely had suitable lighting positions, so this application was limited at first. Lighting rigs were initially a mixture of spotlights and the older floodlights – the latter providing general washes of colour, while the spotlights could highlight specific areas of the stage, and create light and shadow to make actors and scenery looked more three dimensional. Adolphe Appia’s (Q249) concept of stage lighting, mixing diffuse light with directional beams, which he had experimented with at the Festspielhaus, Hellerau (Q63), was becoming available.

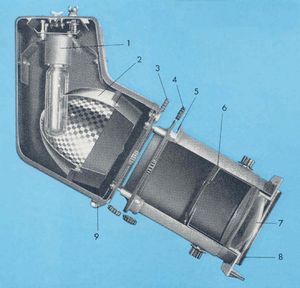

Innovations in the optics brought new types of spotlight, with greater control and different aesthetic possibilities. The ellipsoidal reflector spot (ERS, Q30007) uses a reflector in the shape of an ellipse, gathering the light at a point forward of the lamp itself. At this forward position is a metal plate with a circular hole, known as the gate, and in front of that is a lens. The result is a spotlight that creates a sharp, hard edged beam of light. Anything placed in the gate that changes its shape changes the shape of the beam, allowing masks with different sized and shaped holes, gobos, and shutters. As well as the beam shaping abilities of the ERS spotlight, it could also project a narrower, concentrated beam with little spill light, a great advantage for lighting from front of house.

Another important innovation was the fresnel spot (Q3113), that offered a softer edge than the PC spot, making it easier to blend lighting areas together seamlessly, especially in smaller venues. Beamlights, based on the optics of a searchlight, created soft-edged, narrow and very powerful beams of light, able to cut through the general light on stage. Josef Svoboda (Q91) built entire scenographies with beamlights, and their descendent, the PARcan (Q3147) was the defining light source in rock concert lighting in the 1970s and 1980s.

With the greater control of spotlights, the use of wash lighting gradually reduced, though it didn’t disappear entirely in many theatres until the 1950s and 1960s. The number of spotlights being used increased, so more dimmer circuits were required to take advantage of the detailed, precise lighting that spotlights allowed. The need for accurate and repeatable control of the brightness of each circuit drove the development of lighting consoles.

Spotlighting also led to the development of lighting ‘systems’, the first, and still influential, being that of Stanley McCandless, described in ‘A Method of Lighting the Stage’ (Q65). McCandless set out the fundamental concepts of area lighting (dividing the stage into individually lit areas) and directional colour (slightly different colours from different directions, to provide additional modelling, especially of actors’ faces), which are still in use today.

Spotlighting and the ‘multi-lantern complexity’ is now the dominant form of stage lighting in the Western world, with each lighting state built up from many separate spotlights, lighting defined areas of the stage from many directions and with various colours and textures – the ‘brushstrokes’ that paint the stage picture.