De eerste machinerieën

NEDERLANDS

Machines were an essential part of the staging of Greek dramas, enabling changes of scene. Wagons and revolves were used to bring a dramatic tableau onto the stage, while the rotating periaktoi created rapid changes of location.

An ekkyklêma (Q627, from ekkuklein, to roll out) was a wheeled platform or wagon rolled out of the central door of the skene at the back of the stage, bringing a small scene or tableau into view. Some sources suggest there was a variation in which the wagon revolved, to turn the scene onto the stage. The ekkyklêma was used to bring interior scenes out into the view of the audience, for example murder scenes, which were imagined in the form of living pictures. It was mainly used in tragedies for revealing dead bodies, such as Hippolytus’ dying body in the final scene of Euripides’ play of the same name, or the corpse of Eurydice draped over the household altar in Sophocles’ Antigone. Other uses include the revelation in Sophocles’ Ajax of Ajax surrounded by the sheep he killed whilst under the delusion they were Greeks. The ekkyklêma was also used in comedy to parody the tragic effect. An example of this is in Aristophanes’ Thesmophoriazusae, when Agathon is wheeled onstage on an ekkyklêma to enhance the comic absurdity of the scene.

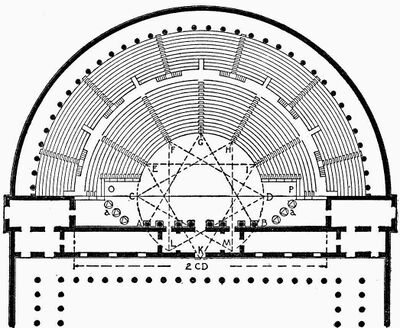

Compared with simply opening the doors or curtain in the skene to reveal the scene, the ekkyklêma offered an important benefit. The semi-circular auditorium of the Greek amphitheatre meant the view of the stage for some members of the audience was very much from the side, so the inner space behind the skene would not have been in view. By rolling or turning the ekkyklêma, it ensured all spectators could see it clearly, while the movement of the mechanism added to the sense of revelation. In Greek theatre there was a strict code forbidding violent deaths being acted out on stage, so the ekkyklêma also provided a permissible means to bring the result of a murder or death onto the stage, with much greater spectacle and dramatic impact than simply having another character report the events.

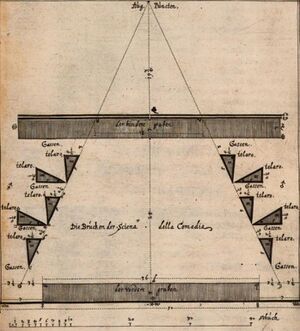

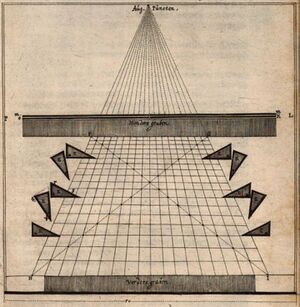

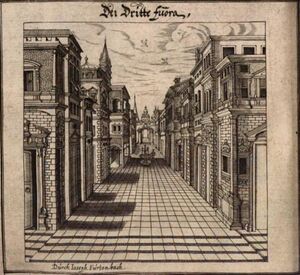

The Greek theatre did not provide a total, illusionistic stage environment. Locations were generic, and denoted by paintings mounted on the skene that were just one part of the overall stage picture. These pictures were called pinakes and could be changed between performances (see story F.01). A different technique was used to change the scene during the performance, if that was required: the periaktoi (Q23827, from the Greek word meaning ‘revolving’ or ‘rotating prisms’ or ‘angular frames’). Periaktoi were three-sided wooded frames covered with painted canvas – a different scene on each side. The frames were fixed to a central, vertical axis embedded in the stage floor, so they could be turned in order to change the location of the scene. This gave then opportunity of visualising different locations depending on the configurations of the periaktoi.

We don’t have detailed records of the placements and mechanisms of the periaktoi, but some recreations of Greek theatres suggest at least two larger periaktoi used at the openings on top of the logneion proskenion on either side of the central opening of the skene. These periaktoi were housed within the skene and were probably turned by hand. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio mentioned the periaktoi in his ten volume De Architectura (Q466) around 13 BCE. In the 5th book he focused on Greek and Roman theatre architecture, where he explained the triangular prisms. In Vitruvius’ floorplan for the Roman theatre, we can see a set of six periaktoi placed in a vee formation on top of the proskenium instead of within the building itself. However, whether these were turned by hand or by an interlocking mechanism made of gears and chains is unclear. The 2nd century Greek grammarian Julius Pollux describes the periaktoi in his dictionary The Onomaticon which was reprinted in 1502. This together with the first illustrated version of De Architectura, published in 1511, may be the reason why the periaktoi and many other theatre machines from Antiquity were revived during the Renaissance. Certainly, theatres of the Renaissance made use of periaktoi, interlocked with either ropes or chains to so they could be turned simultaneously, providing the sense of ‘magical’ transformation that was sought.

Rolling and turning mechanisms were used by the Greek theatres of Antiquity. The ingenuity of these devices and the flexibility they present to achieve quick changes of scene means they have been in use through much of the history of theatre staging since. The mechanical principle of the periaktoi can also be found in modern Trivision billboards, which allows for up to three different messages to be displayed: a modern application of an ancient device.