The first scenography[edit]

In the Greek theatre, the first scenery that was specific to the play comprised painted panels showing generic scenes, mounted on the skene at the back of the stage, or on rotating periaktoi.

The term scenography comes from Greek word scene, meaning ‘stage or scene building’, and grapho, meaning ‘to describe’. Aristotle wrote in his work Poetics about the appearance of skenographia, or painted scenes depicting the place where the action took place. Vitruvius (Q467) stated that Agatharchus (Q433) was the inventor of scenic painting and the first painter known to have used graphical perspective on a large scale. Significant advances in scene painting occurred between the date Sophocles wrote his first play (468 BC) and Aeschylus’ death, twelve years later.

In the early days of Greek tragedy, scenography consisted of a large object placed in the orchestra. It could be an altar, a tower, or a tomb, as happens in Aeschylus’ plays The Suppliants, Seven against Thebes, and The Persians. According to Aristotle, Aeschylus introduced the first painted scenography in the theatre of Dionysos (Q7829) in Athens around 505-456 BC.

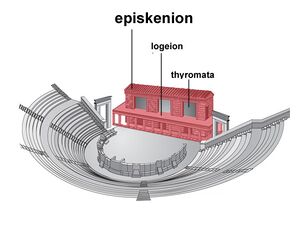

Originally the skene consisted of a small temporary construction where the actor could change his mask and, occasionally, his costume. Its peripheral position and small size did not block the spectator’s view of the surrounding landscape. Gradually the skene gained in size, and by the end of the 1st century BC it was built in stone. In the early, Hellenistic theatre the episkenion was the second floor of the Greek skene. Its facade was perforated by one or more openings called thyromata. These could be fitted with pinakes: painted scenic panels or flats that represented locations during performances and could be easily changed as required, but not during the show. Periaktoi (A.01) could also fit in these openings or just be placed on the stage. These were three-sided painted flats on a triangular base that could rotate in three different positions revealing three different places of action (clouds, mountains, the sea, a garden…) in front of the public. Changes of scenery in tragedies were exceptional, only in comedies were they more frequent and carried out in plain sight.

33 Greek tragedies have survived to the present day, 25 of them take place in front of a temple, palace, or tomb, 4 in front of an army chief’s tent, hut or cave, 4 in an open landscape, 1 on a mountain and 2 in a landscape or sacred place. This means that at least two thirds of the places would correspond to an architectural background that could generically resemble a temple, palace or tomb, literally painted but also in a metaphorical way. The interaction of the different scenic elements with the other spectacular effects (machinery and sound) contributed to generate the illusion.

Many scholars believe ancient artists depicted certain visual phenomena using ‘intuitive perspective’, which means they had no clear system of perspective. However, according to Vitruvius (Q467), Apatorius of Alabanda (31-13 BCE), scene painter of the theatre at Tralles in Lydie, was chastened by the mathematician Licymnios for the incorrect rendering of roofs. He supposedly repainted the perspective to the mathematician’s specifications. The Roman wall paintings at Boscoreale and Pompeii, which are believed to be copies of Greek works, show laws of perspective, because the bottom and top of the picture plane were curved, mimicking how two eyes view space.

Apollodorus Skiagraphos was an influential ancient Greek painter of the 5th century BC who worked as a mural painter and left a technique behind known as skiagraphia, which means he could gradate light and colour, to shade his paintings. That is why he is known as the inventor of chiaroscuro. This shading technique uses hatched areas to give the illusion of both shadow and volume. Pliny called him Apollodius from Athens, the ‘first to give his figures the appearance of reality’.

Other Greeks are known for their scenographies: Anaxagoras (500-428 BC) learned from Agatharchus, Clisthenes and his son Menedemus (450 BC), as well as Epiklytes (274 BC) from the Delos Theatre. Dioskurides (100 BCE) created two mosaic murals that may show pinakes of the Hellenistic stage.

The Greeks of Antiquity established a relationship between theatre and painting – embedded in the term ‘scenography’ – which has been a constant through much of the history of Western theatre. Today, while scenic painting is in a period of decline, the projected image fulfils a similar role – the scene within the scene.