Light and Transformation

Light was vital to the scenic illusion of the Baroque court theatres, distributed around the stage illuminating the scenery as much as the performers. Moving the sources enabled them to be brightened and dimmed in a dynamic stage transformation.

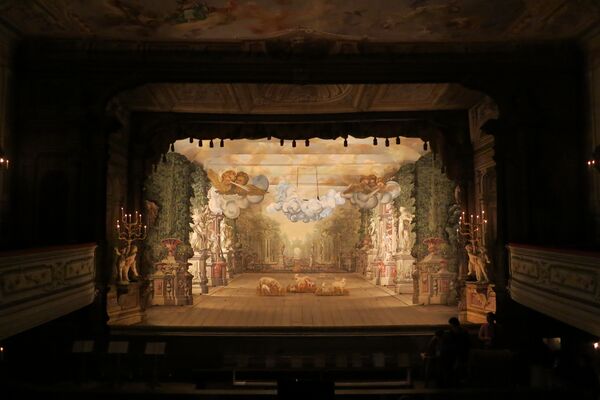

In the Baroque period, the royal court theatres of Europe established an approach to staging that prioritised the perspective illusion: an illuminated ‘magic box’ viewed through the frame of the proscenium arch. During this period, the main light in the auditorium as well as on stage came from oil lamps and candles located on chandeliers over the front of the stage, in sconces around the auditorium, between the scenic wing flats, over the stage between the scenic headers, along the front of the stage (footlights) and at the back of the stage at floor level. The lights in all chandeliers and sconces in the auditorium were lit before the start of the performance and then remained on throughout the performance. The burning time of a wax candle rarely exceeded one hour, and if the performance lasted longer than that, it was necessary to change the candles one or more times during the evening, and to refill the oil lamps. Furthermore, before the 19th century, the wick used in candles was made from a round cotton thread, not braided as they are now, which meant that when the burning wick was too long it was necessary to cut it off to prevent excessive smoke being produced. There are records of complaints by audience members when the candle snuffer entered in the middle of an aria to use scissors to snip the candle from the dangerously long burning wick.

The chandeliers could be lowered to the floor so that new candles could be inserted or the wicks trimmed without needing a ladder. Onstage, the sconces holding the candles were mounted one above the other on poles placed behind each of the scenic flats on either side of the stage. A reflector behind each candle directed the light onto the stage, maximised the brightness. To install new candles in the sconces positioned high up, they were hung on chains so the whole group of sconces could be lowered to the floor.

In some theatres the poles with their sconces could be turned, so when they were directed towards the stage, the light on the stage increased, but if they were turned away from the stage, the stage became darker. With the operation of these lighting columns in each wing linked by a system of ropes, pulleys and capstans below the stage, it was possible to synchronise this lighting control in a simultaneous movement so that the lighting either dimmed or brightened depending on the direction of the lighting columns. Similarly, the footlights at the front of the stage – known as ‘floats’ because of the common method of burning wicks floating in a bath of oil – could be raised and lowered through a slot in the stage floor, so controlling the brightness. In addition to darkening the stage when the footlights were lowered, it was also possible to change the burnt-out candles, or refill oil lamps, while they were out of sight of the audience.

Because the lights in the wings and overhead were close to the painted wing flats and borders, those scenic elements were relatively brightly lit, as were the backcloths when lit by sources set into the floor at the back of the stage. The centre of the stage, by comparison, was dim, being the furthest from any light source. Performers at the front of the stage benefited from the chandeliers overhead, and especially from the footlights – the closest light source for an actor at the front of the stage. The main acting area was therefore the front, with the centre and upstage areas occupied by less important or contextual action, and of course serving as a scenic space – a three-dimensional stage picture with its artificial perspective and illusion of infinite depth.

Although they were an important method of lighting actors, because they could be close and so illuminate brightly, the footlights were disliked by some: Sabbatini (Q13) complained they cast shadows on the scenery, made the actors look pale, and sent fumes into the audience. The footlights would finally be abolished with the advent of electric spotlighting (C.07), except when used as an effect to signal a certain kind of ‘theatricality’. Nevertheless, the Baroque court theatres were able for the first time to control the distribution of light on the whole of the stage, increasing and decreasing its brightness dynamically for each scene. Light had begun to be a means for stage transformation, a use that would continue to develop until the present day.