Stage Engineering Codified

In 1929, the year of a global financial crisis, the stage technician Friedrich Kranich published a book that for the first time systematically presented stage technology, its management and economic planning: Bühnentechnik der Gegenwart.

To this day, the publication, which was supplemented with a second volume in 1933, is regarded as the first comprehensive codification of stage technology in the German language and as a reference book that set historical standards.

Even before the publication of Bühnentechnik der Gegenwart (Q264) by the renowned Oldenbourg publishing house, Friedrich Kranich (Q58) had commented on fundamental questions of stage technology, such as standardisation, in the technical journal Bühnentechnische Rundschau. He had been a member of the professional association of stage managers since its foundation in 1906. Corresponding to the German rationalisation movement of the 1920s, shaped by Frederick W. Taylor’s scientific management and an emerging science of work, the professional association was increasingly concerned with the organisation of stage technology and uniform standards for training and practice. At the same time, efforts were made to popularise stage technology. After 1918, theatres had been municipalised, so the theatrical relevance of stage technology – and its associated costs – had to be justified to the public, rather than relying on courtly privilege, as hitherto. Kranich’s film ‘How an Opera is Made’ was just one attempt amongst others to give an interested audience an insight into the hidden world behind the scenes at the Magdeburg Theatre Exhibition in 1927.

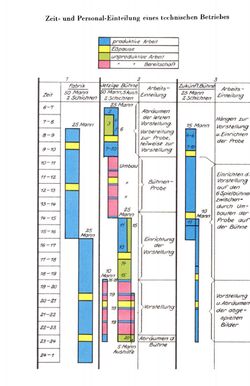

Against this background, the Bühnentechnik der Gegenwart attempts both to codify the place of stage technology in the theatrical artwork and to show its potential for improvement, through the rationalisation of the operation. The self-declared aim is to critically examine the ‘entire technical stage operation’, to show ‘preconditions for the modification of stage houses’, to make ‘suggestions for improvements in machines’, to explain ‘all types of stage set change’ and to determine ‘whether work can be done more economically in the difficult financial situation’. In the course of the handbook, both the influences from stage-technical practice and the efforts to systematise technical stagecraft become clear.

Kranich’s own professional practice and previously published material, mostly taken from the Bühnentechnische Rundschau, form the basis of his book. He was the technical director of the Städtische Bühnen Hannover and the Bayreuth Festival. Although there are a few examples of theatre facilities in the book that point beyond the European continent, the improvement of German stage technology remained the guiding principle. Visual material from Hannover and Bayreuth as well as his modernisation projects therefore form the basis of Kranich’s argument. Illustrations showing practical activities seem to have been staged with Kranich’s own staff. Some right-wrong illustrations, e.g., for carrying bigger pieces of stage scenery in a proper manner, give a textbook character in places.

Nevertheless, the codifications of this practical theatre work, which show ideal functionality, take a back seat to organisational and economic questions of operation. Even the A4 format indicates that this book was intended less as a practical guide. It does better on a writing desk, as did the paper quality, which was too high for daily use in the workplace. The codified predecessors of Kranich’s manual, such as Sabbattini’s (Q13) or Furttenbach’s (Q60), essentially codified the structure of practical knowledge, while the structure of the Bühnentechnik der Gegenwart is oriented towards an abstract systematisation of stage operations. It codifies the practice of the stage manager, rather than the stage worker, who is increasingly involved in scientific and economic planning. Stage logistics, standardisation and ideal solutions were the centre of attention, and means of representation are correspondingly abstract: typologies, charts, and diagrams.

Despite all the systematisation, Kranich remained intent on fitting the codification of stagecraft into a specific genealogy of stagecraft knowledge. An ancestry of important stage practitioners prominently marks the starting point of the handbook, and gives it its legitimacy. First and foremost of these was the icon of bourgeois national cultural ideals in the Weimar Republic: Johann Wolfgang Goethe.

The 19th century saw the industrialisation of stage technologies; Kranich’s work led the industrialisation of stage practices, through the application of scientific and systematic management.